Senior Data Scientist

Eysz, Inc.

is a Senior Data Scientist at Eysz, a med-tech startup that focuses on transforming epilepsy care. He utilizes psychological theory, machine learning, and good-old fashioned research design to separate the signal from the noise.

Jordan's academic work is wide-ranging, focusing on topics such as Hollywood Film, interpersonal relationships, and baseball. He has served as faculty at Indiana University, Saint Joseph's College, and Cornell University.

Eysz, Inc.

Research Narrative

Cornell University, Psychology Department

Saint Joseph's College, Psychology Department

Indiana University - Bloomington, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences

Ph.D. in Psychology - Perception, Cognition, and Development

Cornell University

Executive Master's in Business Administration

Quantic School of Business and Technology

Bachelor of Science in Psychology

Indiana University - Bloomington

Bachelor of Science in Cognitive Science

Indiana University - Bloomington

In baseball, plate umpires are asked to make difficult perceptual judgments on a consistent basis. This chapter addresses some neuro-psychological issues faced by umpires as they call balls and strikes, and whether it is ethical to ask fallible humans to referee sporting events when faced with technology that exposes “blown” calls.

We examined whether dynamic images benefit memory when visual resources are limited. Almost all previous research in this area has used static photographs to examine viewers’ memory for image content, description, or visual attributes. Here, we investigated the short-term retention of brief stimuli using rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) with short videos and static frames of 80, 160, 200, and 400 ms/item. Memory performance for dynamic images was generally better than for comparable still images of the same duration. There was also a strong recency effect for items briefer than 400 ms, which suggests that an optimal duration of about 400 ms may be necessary for dynamic images to be detected and fully processed. Interestingly, we also found that the presence of motion increased performance while the amount of motion did not.

A defining feature of passionate love is idealization—evaluating romantic partners in an overly favorable light. Although passionate love can be expected to color how favorably individuals represent their partner in their mind, little is known about how passionate love is linked with visual representations of the partner. Using reverse correlation techniques for the first time to study partner representations, the present study investigated whether women who are passionately in love represent their partner’s facial appearance more favorably than individuals who are less passionately in love. In a within-participants design, heterosexual women completed two forced-choice classification tasks, one for their romantic partner and one for a male acquaintance, and a measure of passionate love. In each classification task, participants saw two faces superimposed with noise and selected the face that most resembled their partner (or an acquaintance). Classification images for each of high passion and low passion groups were calculated by averaging across noise patterns selected as resembling the partner or the acquaintance and superimposing the averaged noise on an average male face. A separate group of women evaluated the classification images on attractiveness, trustworthiness, and competence. Results showed that women who feel high (vs. low) passionate love toward their partner tend to represent his face as more attractive and trustworthy, even when controlling for familiarity effects using the acquaintance representation. Using an innovative method to study partner representations, these findings extend our understanding of cognitive processes in romantic relationships.

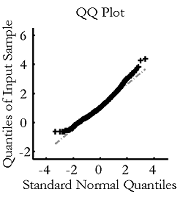

In an article published in Literary and Linguistic Computing, Redfern argues against the use of a lognormal distribution and summarizes previous work as ‘lacking in methodological detail and statistical rigour’. This response will summarize the article’s methodology and conclusion, arguing that while Redfern finds that films are not ‘perfectly’ lognormal, this is hardly evidence worthy of the ultimate conclusion that a lognormal fit is ‘inappropriate’. Perfection is fleeting, and cannot be expected when modeling real data. Reanalysis of Redfern’s methodology and findings shows that the lognormal distribution offers a pretty good fit.

You would be hard-pressed to find someone who does not watch film. Cultures around the globe have embraced the art of the moving image and run with it, creating so many movies that no one person can hope to watch even a majority of them in his or her lifetime. Cinema has become such a fixture in our lives that the average American watches five films in theaters every year. Cinema’s prominent place in society makes it easy to forget that film (in a form we would recognize) has only existed for roughly 100 years. Film has progressed from a technical curiosity to a large-scale form of entertainment that engages viewers from all walks and stages of life. Filmmakers have constantly changed and updated their craft, using trial and error to map out some of the “rules” needed to interface film effectively with the human mind. Several of these rules include matching action, eye gaze, and spatial layout between shots. Determining the bounds of what makes sense to viewers was only the beginning; knowing how to transition effectively between shots is a complex process under constant revision by a community of skilled filmmakers.

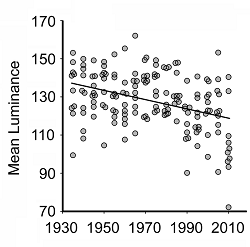

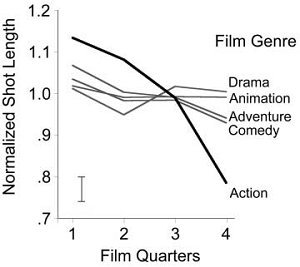

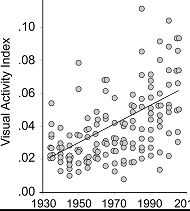

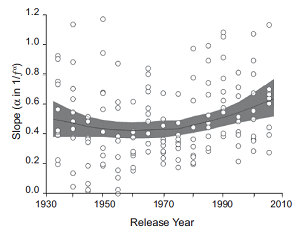

Film theorists have historically examined narrative as the primary influence on the viewer’s experience of a film; however, the growing trend in the cognitive study of film is the study of quantifiable variables and their effect on the viewer experience. This chapter examines research on five of the low-level features present within film: shot duration, shot structure, luminance, visual activity and color. Shot duration has meaningfully decreased with implications for visual momentum. Filmmakers use shot structure (the relative positioning of a shot with a particular duration to other shots within the film) to cater to shifts in viewers’ attention to the film. On-screen activity is examined with regard to how viewers perceive tempo, shifts in time and space, and genre. Like activity, luminance affects viewer perception of the genre of a film, as well as within-film understanding of event boundaries. Color also assists in viewer perception of spatiotemporal shifts. The research in this chapter eschews the traditional view that low-level features are simply an artifact of the narrative; instead, it is unlikely that viewers would be able to fully understand or attend to the narrative without strategic use of low-level features by filmmakers.

This is an amendment to the article "How Act Structure Sculpts Shot Lengths and Shot Transitions in Hollywood Film" by the same authors published in Projections 5(1), summer 2011.

.

.

.

We measured 160 English-language films released from 1935 to 2010 and found four changes. First, shot lengths have gotten shorter, a trend also reported by others. Second, contemporary films have more motion and movement than earlier films. Third, in contemporary films shorter shots also have proportionately more motion than longer shots, whereas there is no such relation in older films. And finally films have gotten darker. That is, the mean luminance value of frames across the length of a film has decreased over time. We discuss psychological effects associated with these four changes and suggest that all four linear trends have a single cause: Filmmakers have incrementally tried to exercise more control over the attention of filmgoers. We suggest these changes are signatures of the evolution of popular film; they do not reflect changes in film style.

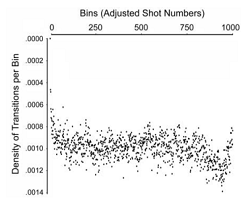

Cinematic tradition suggests that Hollywood films, like plays, are divided into acts. Thompson (1999) streamlined the conception of this largescale film structure by suggesting that most films are composed of four acts of generally equal length-the setup, the complicating action, the development, and the climax (often including an epilog). These acts are based on the structure of the narrative, and would not necessarily have a physical manifestation in shots and transitions. Nonetheless, exploring a sample of 150 Hollywood style films from 1935 to 2005, this article demonstrates that acts shape shot lengths and transitions. Dividing films into quarters, we found that shots are longer at quarter boundaries and generally shorter near the middle of each quarter. Moreover, aside from the beginnings and ends of films, the article shows that fades, dissolves, and other non-cut transitions are more common in the third and less common in the fourth quarters of films.

The structure of Hollywood film has changed in many ways over the last 75 years, and much of that change has served to increase the engagement of viewers' perceptual and cognitive processes. We report a new physical measure for cinema—the visual activity index (VAI)—that reflects one of these changes. This index captures the amount of motion and movement in film. We define whole-film VAI as (1 – median r), reflecting the median correlation of pixels in pairs of near-adjacent frames measured along the entire length of a film or film sequence. Analyses of 150 films show an increase in VAI from 1935 to 2005, with action and adventure films leading the way and with dramas showing little increase. Using these data and those from three more recent high-intensity films, we explore a possible perceptual and cognitive constraint on popular film: VAI as a function of the log of sequence or film duration. We find that many “queasicam” sequences, those shot with an unsteady camera, often exceed our proposed constraint.

In two experiments we determined the electrophysiological substrates of figural aftereffects in face adaptation using compressed and expanded faces. In Experiment 1, subjects viewed a series of compressed and expanded faces. Results demonstrated that distortion systematically modulated the peak amplitude of the P250 event-related potential (ERP) component. As the amount of perceived distortion in a face increased, the peak amplitude of the P250 component decreased, regardless of whether the physical distortion was compressive or expansive. This provided an ERP metric of the degree of perceived distortion. In Experiment 2, we examined the effects of adaptation on the P250 amplitude by introducing an adapting stimulus that affected the subject's perception of the distorted test faces as measured through normality judgments. The results demonstrate that perception adaptation to compressed or expanded faces affected not only the behavioral normality judgments but also the electrophysiological correlates of face processing the window of 190–260 ms after stimulus onset.

Reaction times exhibit a spectral patterning known as 1/f, and these patterns can be thought of as reflecting time-varying changes in attention. We investigated the shot structure of Hollywood films to determine if these same patterns are found. We parsed 150 films with release dates from 1935 to 2005 into their sequences of shots and then analyzed the pattern of shot lengths in each film. Autoregressive and power analyses showed that, across that span of 70 years, shots became increasingly more correlated in length with their neighbors and created power spectra approaching 1/f. We suggest, as have others, that 1/f patterns reflect world structure and mental process. Moreover, a 1/f temporal shot structure may help harness observers’ attention to the narrative of a film.

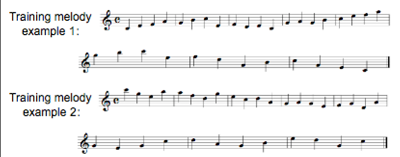

Evidence suggests that sparse coding allows for a more efficient and effective way to distill structural information about the environment. Our simple recurrent network has demonstrated the same to be true of learning musical structure. Two experiments are presented that examine the learning trajectory of a simple recurrent network exposed to musical input. Both experiments compare the network’s internal representations to behavioral data: Listeners rate the network’s own novel musical output from different points along the learning trajectory. The first study focused on learning the tonal relationships inherent in five simple melodies. The developmental trajectory of the network was studied by examining sparseness of the hidden layer activations and the sophistication of the network’s compositions. The second study used more complex musical input and focused on both tonal and rhythmic relationships in music. We found that increasing sparseness of the hidden layer activations strongly correlated with the increasing sophistication of the network’s output. Interestingly, sparseness was not programmed into the network; this property simply arose from learning the musical input. We argue that sparseness underlies the network’s success: It is the mechanism through which musical characteristics are learned and distilled, and facilitates the network’s ability to produce more complex and stylistic novel compositions over time.

In film, a ‘cut’ is a transition between two continuous strips of motion picture film, or ‘shots’. These transitions can dissolve one film strip into the next, or be an abrupt stop between the two shots. How cuts have increased in frequency since the beginning of cinema and how their arrangement form structure across groups of shots is the focus of this study. In order to examine this, films were obtained from 3 genres (action, comedy, drama) and 4 years (1945, 1965, 1985, 2005), one film per genre per year. Luminance and color information were digitally sampled and imported into a Matlab-programmed ‘cut detector’ to predict where cuts occurred within the given film. The program detected hard and soft cuts, which were then manually confirmed or rejected. Additionally, ranges of flagged frames were processed to identify missed cuts, resulting in a list of all the frame numbers at which cuts occur in each film. The results show that mean shot length has decreased over the years. Auto-correlation computation of shot length pairs shows that shot pairs are positively correlated, across both variables of genre and year; this reveals that structure is present across groups of shots in the same pattern of shot length sequences. This finding suggests that there is much more structure to narratives and to seemingly intuitively-placed cuts than one may think.

In five experiments, we examine the neural correlates of the interaction between upright faces, inverted faces, and visual noise. In Experiment 1, we examine a component termed the N170 for upright and inverted faces presented with and without noise. Results show a smaller amplitude for inverted faces than upright faces when presented in noise, whereas the reverse is true without noise. In Experiment 2, we show that the amplitude reversal is robust for full faces but not eyes alone across all noise levels. In Experiment 3, we vary contrast to see if this reversal is a result of degrading a face. We observe no reversal effects. Thus, across conditions, adding noise to full faces is a sufficient condition for the N170 reversal. In Experiment 4, we delay the onsets of the faces presented in noise. We replicate the smaller N170 for inverted faces at no delay but observe partial recovery of the N170 for inverted faces at longer delays in static noise. Experiment 5 demonstrates the interaction in low contrast at a behavioral level. We propose a model in which noise interacts with the processing properties of inverted faces more so than upright faces.

Dr. Gül Günaydin's lab at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey looks a how romantic attachment changes people's thoughts and behaviors. In collaboration with Gül, I'm part of a project to see how romantic attachment changes the perceptual representations. In short, we wondered if falling in love with someone can change how you see them? Our study "Reverse Correlating Love", provides evidence to suggest that Turkish women in passionate relationships see their partners in different ways.

Reverse Correlation is an intriguing technique pioneered in the social domain through work out of Ron Dotsch's lab. It allows participants to choose between two faces made of structured noise to say which one looks more like a target stimulus. The selections are then averaged, to produce a final face that should have features the participant picked out of the random faces. A simple version is to ask participants choose which of two randomly generated faces is happier, and then construct a composite happy face from their choices.

Work is underway to utilize this paradigm in other contexts, including work with Dr. Jeremy Cone at Williams College to see how visual representations change once someone is faced with new information.

After my Industrial/Organizational Psychology class at IU Bloomington concluded in the fall of 2013, students wanted to learn more about how they could apply psychology in the workplace. Unfortunately, there wasn't anything for business minded psychology students. After some research into successful programs, we founded ADAPT Consulting @ IU , a group that does volunteer consulting work for local businesses and nonprofits.

I typically work from my home office in Indiana, which is in the Eastern Time Zone.

You can check out what we're doing at Eysz by visiting eyszlab.com .